CLAUSHOLM

THE JUDICIAL SYSTEM AND THE ESTATES

By ph.d. Dorte Kook Lyngholm, Historical Museum of Northern Jutland

In the 18th century Danish estate owners were a key and integral part of the absolute monarchy’s judicial system in rural areas. The owners of manor Clausholm, which held the right of jurisdiction, the so-called birkeret, within the estate lands, played an extremely active role in the administration of justice: for example, as prosecutor and fines collector in criminal cases. This article shows how the estate owners’ independent room for manoeuvre in the judicial system was deployed both for the demonstration of power and for the distribution of mercy to the residents of Clausholm, who had fallen foul of the law.

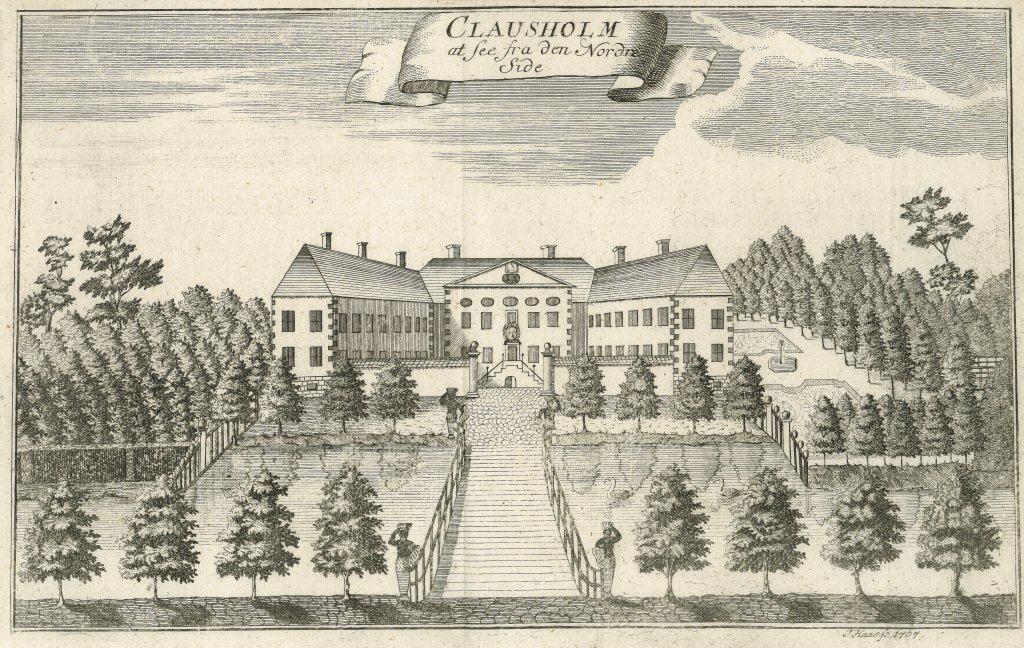

The Manor House of Clausholm seen from the south-east. The impressive main building on Clausholm estate was built in the 1690s by Conrad Reventlow, whose marble bust still resides over the main entrance. The three-winged baroque manor was taken over by king Frederik IV in 1718, who further more added two wings to the south side of the building as seen in the picture. On the same occasion, Clausholm got its present color, as the original red-painted walls became white-painted. Photo: Bent Olsen.

The owners of Clausholm in the mid-18th century

Christian von der Maase’s coat of arms. Christian von der Maase and subsequently his wife Magdalene Susanne von der Maase (born Numsen) owned Clausholm in the years 1743-57. Christian, born with the surname Masius, was enobled in 1712 with the name ‘von der Maase’. The practical consequence of having the legal nobility privileges meant that Christian von der Maase got a very central position in the local law enforcement at Clausholm. Copyright: Danmarks Adels Årbog, bd. 30, 1913, p. 393.

In modern times the State automatically has at its disposal a sophisticated administrative and legal system in rural areas. However, during a very long period of Denmark’s history, it was a completely different story and, right up to the mid-19th century, the Crown had only a very limited number of local officials in rural areas. So, to a great extent, the State based its local management and judicial administration on the existing local authorities: the estate owners.

As this system was reaching its peak in the mid-18th century, the Crown had just sold Clausholm, following the death in 1743 of the former owner and dowager queen, Anna Sophie Reventlow. The new owner of Clausholm and the estate was Christian von der Maase (1694-1753), who had previously owned the estates of Ravnstrup, Fuglebjerg and Raschenberg (now Juelsberg) on Funen and Zealand. He had been awarded the honorary title of Councillor of State and belonged to the first noble generation of his family. His father had made a name for himself as a court preacher, and all his children had subsequently been raised to the peerage by the king. After his death in 1753, his wife Magdalene von der Maase (née Numsen) (1689-1758) took over Clausholm, before putting it up for sale shortly before her death.

The next owner was the Norwegian nobleman and lieutenant colonel, Matthias Vilhelm Huitfeldt (1725-1803), who bought Clausholm in 1757 after leaving the army. During his time at Clausholm he was given several notable positions in the regional administration of the Danish absolutist state. Among these were important positions included those of prefect for the diocese of Viborg [Da: stiftamtmand] and sheriff of Skivehus and Hald counties [Da: amtmand]. In 1779 he was awarded the honorary title of Privy Councillor [Da: gehejmekonferensråd]. Huitfeldt and his wife, Charlotte Emerentia Raben (1731-1798) held on to Clausholm until the end of the century, after which it was sold to their son-in-law in 1800.

Clausholm as an administrative centre

Portrait of Matthias Vilhelm Huitfeldt. The Norwegian nobleman Matthias Vilhelm Huitfeldt owned Clausholm in the years 1758-1801. He was originally destined for a military career, but instead he became a landlord and official in the regional government of the monarchy. He was appointed as both prefect over the diocese of Viborg and sheriff over Hald and Skivehus counties. He became the longest seated landlord at Clausholm in the 18th century, and he and his wife Charlotte Emerantze Raben are buried in two large marble sarcophaguses in Voldum Church. Copyright: Clausholm painting. Photo: Michael Green.

These estate owners were the supreme authorities on one of the largest estates in Denmark. By the mid-18th century Clausholm estate was a vast, cohesive collection of copyholds south east of Randers, which accommodated roughly 1,000 residents spread over 21 villages. The estate was a well-established entity, whose residents and villages with their farms and houses were bound together by a well-oiled administrative machine. This administration was headed by a bailiff or steward of the manor [Da: ridefoged]: initially Jens Hutfeldt Bagge, succeeded by Johannes Bornemann. These two men were the estate owners’ representatives in almost all dealings with Clausholm’s residents.

The administration encompassed a wide range of tasks related to the day-to-day economy and operation of the estate. These many different aspects of estate management were evident every year in May, when accounts for Clausholm’s overall budget were presented. The income part of the accounts included, for example, the collection of the tenants’ annual dues on farms and houses [Da: landgilde and huspenge] the copyhold fee for taking over a house or farm, the pannage fees, the Church tithes and the profits from the estate’s lime and brick factory.

The stewards of the estate were not only responsible for a wide range of the estate’s private tasks, but also constituted a cornerstone of the State’s local administration. At Clausholm, as on Denmark’s other privately owned estates, the estate owners held responsibility for central government tasks: for example, local tax collection. The estate owners were entrusted not only with the administrative tasks, but also with the financial responsibility, and were personally liable to the royal treasury if a tenant failed to pay his taxes. Another of the State’s major tasks administered by the estates was the conscription of soldiers. The estate owners were responsible for deciding which of the estate’s residents should do military service.

The judicial system at Clausholm

The estates also played a key and integral role in the absolute monarchy’s local judicial system. The estate owner, Matthias Huitfeldt descended from an old noble family and, as already mentioned, his predecessor, Christian von der Maase belonged to the first generation of his family’s noble status. In terms of local law enforcement in the rural areas, this was of crucial importance, because an estate owner’s authority depended on whether or not he belonged to the nobility.

Front page of estate account from Clausholm 1757-58. The central office of Clausholm was the center of a large administrative apparatus in the middle of the 18th century. This administration included both the operation of the goods and a number of administrative and legal tasks which the estates carried out in rural areas on behalf of the state. On the income side of the estate accounts, you will find payments of the farmer’s taxes to the landlord side by side with royal royalties collected and court sentences imposed by the local courts. Copy: Clausholm estate archives, accounts with appendix 1757-63 A (Rigsarkivet, Viborg). Photo: Dorte Kook Lyngholm.

By the mid-18th century, about 90% of Denmark’s population lived in rural areas, and about half of this group lived on estates owned by noblemen. (The remaining rural population lived on estates, which were owned by the crown, middle-class estate owners or institutions). For the residents of Clausholm, and residents on other noble estates, it meant that they were subject to an estate owner with a number of privileges that carried a number of specific tasks in the local judicial system.

One of these privileges was the right of prosecution and punishments, the so-called hals- og håndsret. The estate owners were not only entitled, but also duty bound to prosecute crimes committed on their estates. During the 18th century this role evolved into a kind of precursor of today’s public prosecution authority. It was the responsibility of the estate owners to see that cases were brought before the courts whenever a breach of the criminal law had been committed on their estate. To a certain extent, the hals- and håndsret also gave estate owners the right (and the responsibility) of implementing any sentence of corporal punishment handed down by the local courts in rural areas.

Another of the significant legal privileges the noblemen had was the right of pecuniary penalties, the so-called ‘sagefaldsret’, which gave estate owners the right to collect a share of the fines that were imposed for misdemeanours on their estates. In this context, estate owners had substantial room for independent manoeuvre, since they had the right to strike bargains on their subordinates’ fines: in other words, to reduce or cancel the fine, which was otherwise prescribed by law.

Whereas the above mentioned right of pecuniary penalties (sagefaldsret) and right of prosecution and punishments (hals- og håndsret) were legal privileges for the entire nobility, only a special, privileged number of noble estate owners had the right of jurisdiction, the so-called ‘birkeret’. Birkeret meant that the estate was established as an independent judicial community, in which the estate’s residents were not subject to the jurisdiction of the regular lower-level rural courts comparable to the Quarter Sessions [Da: herredsret]. Instead, they were subject to the jurisdiction of the estate’s own court, the birketing, for which, in the 18th century, the estate owner selected and appointed the judge. The estate court functioned on the basis of the same legislation as the regular rural courts , and at no time did Danish estate owners have the right personally to pass judgements at these courts.

Nonetheless, the legal privileges invested the estate owners with significant influence on the local administration of justice on their estates. The judicial process in the 18th century was thus part of a complex and hierarchical system, which invested with the estate owners the ability to carry out punishments or be merciful, thus reinforcing their status and power. When residents at the Clausholm estate were up against the law, they would face the estate owner’s representative in the – far from neutral – arena of the birketing chamber at Clausholm.

Engraving of Clausholm’s main building from 1767. When the Danish Atlas was published in the 1760s, it was repeatedly stated in the description of Clausholm that it was a “very old manor”. In the middle of the 18th century, the estate was not only among the oldest in the country, but also among the largest. The estate farms produced 940 barrels of grain per year on land, which was distributed in an area south of the main farm in Galten, Sønderhald and Øster Lisbjerg shires. The estate stretched over 116 farms and 56 houses spread over 21 villages and had a population of around 1,000 people. Copyright: Erik Pontoppidan: The Danish Atlas, bd. IV, 1768.

Owners of Clausholm in the 18th century

1718-1730: Fredrik IV (1671-1730)

1730-1743: Anna Sophie Reventlow (1693-1743)

1744-1753: Christian von der Maase (1694-1753)

1753-1758: Magdalena Susanna von der Maase, (born Numsen) (1689-1758)

1758-1800: Matthias Vilhelm Huitfeldt (1725-1803)

Further reading:

Holsten, H. Berner Schilden (1967): ‘Clausholm’, in Aage Roussell (ed.): Danske Slotte og Herregaarde, 2nd edition vol. 14, Hassings Forlag Copenhagen, pp 77-98.

Lyngholm, Dorte Kook (2013): Godsejerens ret. Adelens retshåndhævelse i 1700-tallet – lov og praksis ved Clausholm birkeret. Dansk Center for Herregårdsforskning and Landbohistorisk Selskab.

Lyngholm, Dorte Kook: ‘Ret og magt på godset’, on: www.danskeherregaarde.dk

Løgstrup, Birgit (1983): Jorddrot og offentlig administrator. Godsejerstyret indenfor skatte- og udskrivningsvæsenet i det 18. århundrede. The Danish National Archives and GADS Forlag.

Løgstrup, Birgit: ‘Godsejerstyret’, on: www.danmarkshistorien.dk

GUIDED TOUR