LORD OF THE MANOR – AND THE LIFE OF THE PEASANTS

By Mikael Frausing, Danish Research Centre for Manorial Studies

The Stjernholm family owned the manor Kjeldgård for 100 years from 1709 to 1810. The estate was an economic, legal and social framework for the rural community and, as “lord of the manor”, the Stjernholms held power over other people. The estate owner’s commands had a huge influence on the living conditions of the peasants. In this article, you can read about how the Stjernholm family tackled their role as estate owners, what ideas they had, and how it affected the peasants under the estate.

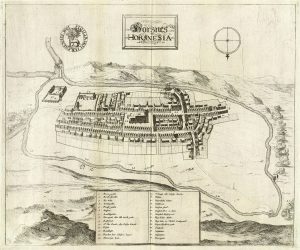

Horsens and Stjernholm Castle. Herluf Jensen, who bought the manor house Kjeldgård in 1709, was originally from Horsens, and when he was enobled many years later, he took the name of the castle in his home town: ‘Stjernholm Castle’, which he must know from his childhood. Resen’s Atlas Danicus depicts Stjernholm Castle just outside of Horsens (No. 17), but the castle might already have been demolished before the engraving was produced around 1675 – the stones from Stjernholm Castle were used for the construction of the new manor house Bygholm just before 1700. Engraving, Horsens, Resens Atlas Danicus, The Royal Library.

Herluf Jensen Stjernholm (1679-1759) – manor and noble title

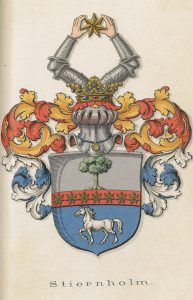

In 1747 Herluf Jensen was adopted and was named Stjernholm. It was a step up the social rank and an emphasis on familys progress over the past decades. Many of the members of the family made military career and the name Stjernholm was renowned amongst officers in the 19th century. Dansk Adels Aarbog 1929, p. 277ff.

Herluf Jensen was the son of a merchant from Horsens. In his youth he had worked as a scribe for various shire authorities in Jutland. However, by 1709 he was wealthy enough to buy the manor Kjeldgård, and the following year he married Marie Overgaard, a wealthy widow who had been born on the manor Quistrup.

The acquisition of Kjeldgaard elevated Herluf Jensen to the status of “lord of the manor”. In 1734 he bought yet another manor: Ørndrup on the nearby island of Mors. His intention was to hand it over to his eldest son, but both he and, later, two other sons died at a young age. Instead, Ørndrup was passed on to the youngest of five sons, Jens Stjernholm, who had made a career as a major in the cavalry.

Herluf Jensen ran Kjeldgård himself until, in his old age, he passed on the estate to his eldest surviving son, Rasmus. In addition to his sons, he had two surviving daughters, who had married well as the wives of priests. Herluf Jensen had consolidated his social ascent, paving the way for his children.

In 1747 Herluf Jensen was ennobled and took the name of Stjernholm. This was a step up the social ladder and emphasised the family’s progress over the previous decades. The noble title brought rank and status, and both surviving sons had been firmly placed as estate owners.

Rasmus Stjernholm (1712-1777) inherited the manor and the title of noblility in 1755. The same year he married Anne Kirstine Øllegaard Hvas (1731-1783). Photo: Dansk Adels Aarbog 1929, p. 277ff.

Rasmus Stjernholm (1712-1777) – lord of the manor

Kjeldgård was neither one of the largest nor one of the smallest manors. But, by all accounts, it was a well-run estate, when Rasmus Stjernholm took it over from his father in 1755. In his father’s time, the number of copyhold farms was expanded. The valuable church tithe had also been acquired, constituting a significant portion of the estates’s revenue.

In tune with the ideal of the age, Kjeldgård had consolidated its copyhold farms closely around the manor itself. In the three villages of Selde parish, virtually all the copyhold farms belonged to Kjeldgård, along with a handful of farms in the neighbouring parishes. The ownership of the copyhold farms gave the estate owner all-powerful influence in the parish and significant power over the peasants lives.

Rasmus Stjernholm concentrated on consolidating the estate’s operations and perpetuating the family’s new-found status. That also involved marrying well. In this respect Rasmus almost went off the rails when in his youth he sired an illegitimate child with a clergyman’s daughter. He collected himself and later married the daughter of an neighbouring estate.

Like Rasmus Stjernholm, Anne Kirstine Øllegaard Hvas (1731-1783) had parents who had worked their way from tenants to landowners. Photo: Dansk Adels Aarbog 1929, p. 277ff.

As estate owner, Rasmus Stjernholm was aware that the future revenue depended on the long-term performance of the copyhold farms. The tenants should not be drained dry by high payments, as was the case, for example, in the neighbouring manor of Jungetgård.

Frederik Stjernholm (1760-1810) – the new main building

Frederik Stjernholm was only 23 years old when he took over Kjeldgård from his mother, who had run the estate as a widow for a number of years. With a certain degree of self-awareness, the young man embarked on the construction of a new manor house. The new Kjeldgård was completed in 1787: a three-winged, red brick building in an architectural style typical of manor houses in Central and West Jutland in the late 18th century.

Frederik Stjernholm wanted to stand out and highlight the family’s progress, and the new main building was an effective way to indicate his status. It was all about luxury. The main building’s three-winged floor plan was based on the ideals of the Baroque, and a moat around the building would stress the family’s distance from the outside world. The magnificent adjacent park was a demonstration of luxury that was only within reach of the owner of the manor house.

The Stjernholms at Kjeldgård 1709-1810

1709-1755: Herluf Jensen Stjernholm

1755-1777: Rasmus Stjernholm

1777-1783: Anne Cathrine Stjernholm (née Øllgaard Hvass)

1783-1810: Frederik Stjernholm

In other words, Frederik Stjernholm’s investment was above all an expression of the status and progress of the Stjernholms. Like his father, he regarded it as almost natural, that he as lord of the manor had power over (and responsibility for) the estate’s subordinate peasants. The new main building was clearly built for the family’s continued affiliation with Kjeldgård.

But new winds soon blew over society, and Frederik was to be the last Stjernholm at Kjeldgård.

The sale of the copyhold farms and the phasing out of Kjeldgård

A number of major agricultural reforms in the late 18th century made it attractive for estate owners to sell off large numbers of copyhold farms. The former tenants became freeholders and thus independent farmers. However, they now had to pay interest and principal on the loans they took to buy the farms from the estate.

At Kjeldgård, the first steps were taken in the mid-1790s and continued with occasional sales of copyhold farm for the next 15 years: in particular, farms in the neighbouring parishes, but also in Selde parish. 1810 saw the start of extensive sales of Kjeldgård’s copyhold farms, but this was also the year, in which Frederik Stjernholm died, and Kjeldgård was taken over by a consortium, which completed the sales.

Kjeldgård was now a large farm – easily the largest in the parish – but the farm was no longer the centre of a vast estate, where the estate owner had power and authority over (and felt responsible for) the lives of the peasants.

Interestingly enough, in 1818, when the eldest son, Søren Stjernholm, the fourth generation of Stjernholms, bought Gammellund on Mors, this was also a case of a former manor, which due to sell-offs and partitioning had been reduced to a large farm. In Central and West Jutland, the age of the manorial system was drawing to a close.

On this plan over the buildings of Kjeldgård, the new, three-winged manor house and the pleasure garden to the east are clearly visible. The large home farm to the south no longer exists. Map of Kjeldgård (section), 1815. Geodatastyrelsen.

Further reading:

The article is based on Asbjørn Romvig Thomsen’s work on the lives of peasant farmers in three parishes on the northern tip of Salling. See:

A.R. Thomsen (2011), Lykkens smedje? Social mobilitet og social stabilitet over fem generationer i tre sogne i Salling 1750-1850, Landbohistorisk Selskab

A. R. Thomsen, ‘Den gode, den griske – og den gale godsejer’ in: Det pryder vel en Ædelmand, ed. S. S. Boeskov, D.K. Lyngholm and M. Frausing, Dansk Center for Herregårdsforskning, pp. 83-102.

ACCESS TO COURTYARD

AGRICULTURE