THE SURVIVOR

By Christian Ringskou, MA, Ringkøbing-Skjern Museum

When rural reforms towards the end of the 18th century unleashed a wave of speculation and shut-downs, leading to the demolition of nearly all the manor houses in West Jutland, some of them managed to survive. With its status as an indivisible entailed estate, the manor Lønborggård, south of the River Skjern delta, was one of the few in the region to remain a considerable estate.

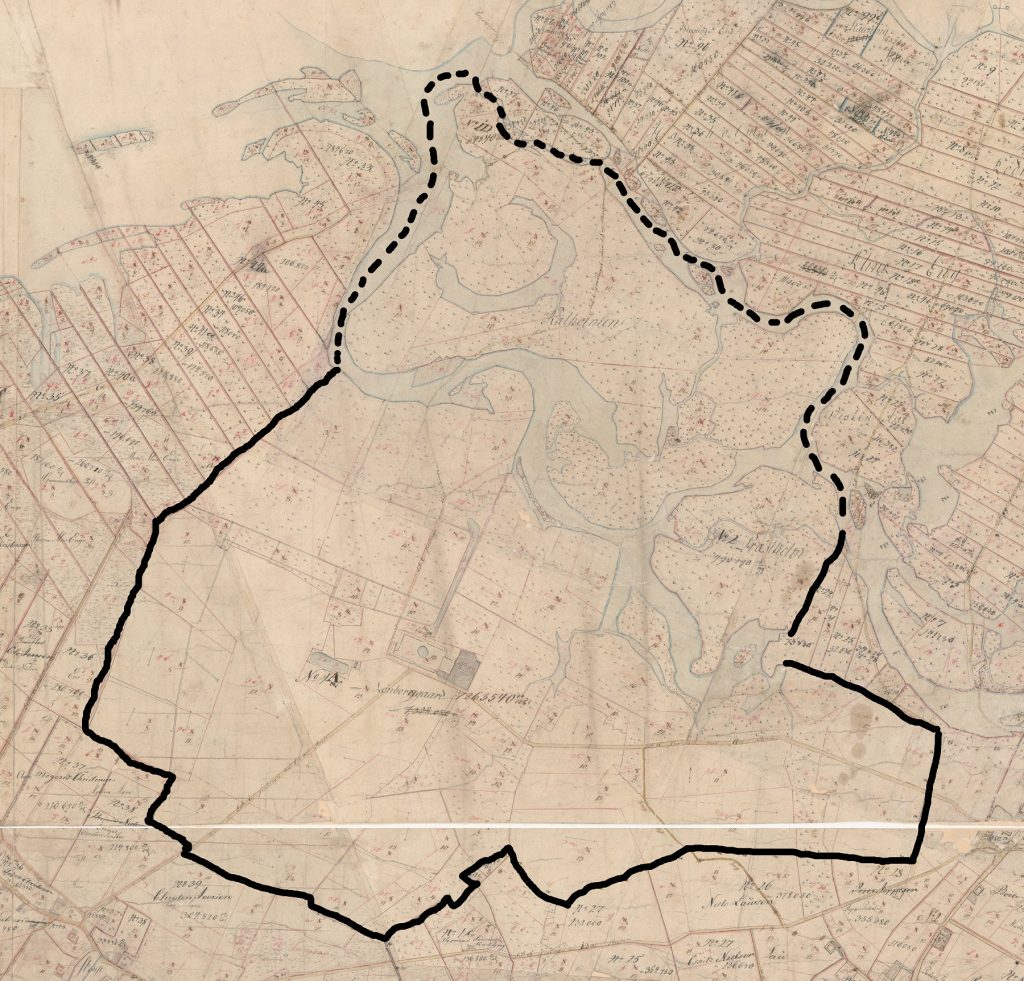

Detail of the so-called original 1 map of the northern part of Lønborg parish 1818. The main estate land of Lønborggård as it looked after Niels Jermin’s renewal in 1792-93.

The largest manor house in the shire

In 1975, a local historian, H.K. Kristensen concluded his description of Lønborggård with the following: “Unlike most estates in West Jutland, Lønborggård escaped being split up into small holdings. It covers 3000 acres of land [Da: 2,186 tønder land] … a huge estate, the biggest estate in the shire.”

Lønborggård’s prolonged survival as a manor was not simply a matter of finance. Culturally too, the estate’s owners retained a position outside the ordinary rural society. Viggo Hedegaard Thomsen, who was present when the owner, Ernst Tranberg sold off Lønborggård in January 1940, described how Tranberg and his manager attended the event in newly polished riding boots. “In my opinion, the dear Mrs Thora (b. Hoppe) and the sturdy, on that occasion somewhat melancholic estate owner, represent the last standard bearers of West Jutland manorial culture.”

Lønborggård, the entailed estate

Lønborggård’s history as one of West Jutland’s major manors dates back to the Reformation in Denmark (1536), when the bishop’s estate in Lønborg was amalgameted with that of the king. The crown later sold the estate, and in 1750 it came into the possession of Christen Hansen, a tea and porcelain merchant.

Workers at Lønborggård photographed on the steps in front of the main building, perhaps in the 1930s (?) Ringkøbing-Skjern Museum.

As a true child of the 18th century and its new opportunities, this lowly born West Jutlander had earned a fortune from trade in China, and it was now time to consolidate his new status and become a the owner of a landed estate. Christen Hansen bought more property for Lønborggård and in 1757, three years before his death, he established one of only three entailed estates in Ringkøbing Shire [Da: Ringkøbing Amt] out of Lønborggård itself and the smaller manor Skrumsager.

The establishment of the entailed estate meant a number of limitations in terms of the property rights of Hansen and subsequent estate owners. On the other hand, the pinnacle of the tea and porcelain merchant’s life’s work was protected from crumbling. Subsequently, Lønborggård would be passed on undivided. Copyhold farms under the estate could not be sold off and in the event of bankruptcy creditors could not seize the manor.

Lønborggård was passed on to Hansen’s nephew, Niels Hansen, and then to the latter’s son-in-law, Niels Jermiin. Jermiin became the owner in 1787, just as a new era was sweeping across the manors of West Jutland. Formerly, in order to obtain the socalled ‘manorial freedom’ and become tax exempt, manors were required to uphold a minimum of cadastral copyhold land to the equivalent of 30-50 farms [Da: 200 tønder hartkorn]. In accordance with a large body of laws in 1788, authorities routinely granted manors an exemption from this requirement. Thus an important basis for maintaining the old system disappeared. Everywhere, land was sold and parcelled out, and before long the actual manors underwent the same treatment.

Niels Jermiin also saw opportunities for selling and parcelling out. Besides Lønborggård, he owned several other manors, which he phased out around 1800. However, when it came to the entailed estate, he had to take other matters into consideration.

Renewal

In 1792-93, Jermiin paid for an expensive and comprehensive renewal, so the old patchwork of scattered plots of earth and meadow belonging to both the copyhold farms and the manorial farm itself were consolidated into rational plots. He even took on (with an uncertain expectation of royal building aid) the cost of moving and erecting a number of farms, where the old buildings were located too far away from the new farmland.

Workers at Lønborggård photographed in the courtyard. Note that the horses have been joined by the first tractor. Ringkøbing-Skjern Museum

The history of the renewal is wellknown and often highlighted as a prime example of the humane lord of the manor lending a helping hand to his peasants as they approached a new era. But Jermiin’s actions were not entirely altruistic. There is no doubt that he handed over good meadows and fields to his tenants and took less in return. But – and this is important – he had the arable land of the home farm, which had previously been dispersed, consolidated into a coherent, rational cadastre.

The peasants also had their farms better consolidated, but there was no question of revoking the copyhold. That meant they still had to do the bulk of the work on the fields of the manor, and in this context Jermiin was less self-sacrificing. At any rate, in 1796, and by their own admission, the “poor, repressed peasant workers” complained about their workload on the new streamlined estate. But nothing came of it.

In other words: since Niels Jermiin could not sell Lønborggård, neither the manor nor the copyhold farms, he instead devoted himself to optimising the performance of the estate on the basis of the old manorial system.

After the entailed estate

In principle, an entailed estate could be neither shared nor dissolved. But principles are one thing; realities are something else. In Jermiin’s time, changes were made to the holdings of the entailed estate. The small manor Skrumsager was dissolved and was replaced by Lønborggård’s former big brother, Lundenæs. During the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, Lundenæs Castle had been the king’s huge estate on the banks of the rich River Skjern, but it was only a reflection of its former glory when, in the 1770s, it came into the possession of Lønborggård’s owners.

In 1811, Jermiin’s son-in-law, Christian Frederik Otto Benzon inherited Lønborggård. In 1813, Benzon was granted royal permission to revoke the entailed estate, and the estate was sold to the investor and speculator, Frederik Juul. The fate of Lønborggård was apparently sealed, but timing was bad. 1813 was the year of a spectacular national bankruptcy. The bubble burst in the 1810s. Crisis, bankruptcies and a frozen credit market replaced 25 years of soaring prices and frenzied activity. Frederik Juul was one of the first to run out of steam.

Benzon had to buy back Lønborggård and, in a market without buyers, and contrary to his original plans, he also became one of a number of landowners who invested in Lønborggård’s continued development. Between 1838 and 1839, he constructed a new main building still to be seen; he landscaped plantations; and ran a significant dairy on the estate.

In 1841, Andreas Grøn Tranberg took over the estate. Now, agriculture was experiencing better times once again, and the economic boom of the following decades did not encourage phasing out. Far from it. Not until 1848 – and it was unusually late in West Jutland – the copyhold farms were finally sold off, but in this case it was much more to do with adjusting to new times. The East Danish manors also sold off huge numbers of copyhold farms from about 1850.

The Tranbergs owned Lønborggård for three generations. Thus we come to the age of the last owner, Ernst Tranberg in his shiny riding boots, who in 1940 was the last standard bearer of “West Jutland manorial culture.”

Lønborggård, the survivor

The estate’s status as an entailed estate cannot be the only explanation for Lønborggård’s survival through the most frenzied wave of closures, whilst other manors in West Jutland disappeared. For example, another entailed estate, the huge barony of Rysensteen was dissolved and the estate phased out between 1797 and 1809.

The proficiency of the estate owners, their choices and priorities were important, and coincidences were a factor. However, it is characteristic that investment was made into the entailed estate of Christian Hansen, the tea and porcelain dealer. It is equally characteristic that the estates of Lundenæs, Østergård, Engelsholm and Skrumsager were all parcelled out and closed down by the very same lord of the manor who held on to Lønborggård.

Recommended reading

H.K. Kristensen: Nørre Horne Herred 1975

Palle Fløe og O. Nielsen: Historiske Efterretninger om Lønborg og Egvad Sogne 1878

Palle Fløe: ”Udskiftningen af Lønborggaard Gods i Aarene 1792-93” in Hardsyssels Aarbog 1921 pp. 112-40

Flemming Jerk: ”Ringkøbing Amts herregårde gennem godsslagtningens tidehverv” in Hardsyssels Årbog 1958 pp. 100-151

Viggo Hedegaard Thomsen: ”Af en vestjysk herregårds saga” Kronik in Ringkøbing Amts Dagblad 10. december 1973